Gout – Gouty Arthritis

Gout has become more common in recent decades, affecting about 1–2% of the Western population at some point in their lives. The increase is believed due to increasing risk factors in the population, such as metabolic syndrome, longer life expectancy and changes in diet. Gout was historically known as “the disease of kings” or “rich man’s disease”.

Signs and symptoms

Gout presenting in the metatarsal-phalangeal joint of the big toe: Note the slight redness of the skin overlying the joint.

Gout can present in a number of ways, although the most usual is a recurrent attack of acute inflammatory arthritis (a red, tender, hot, swollen joint).[2] The metatarsal-phalangeal joint at the base of the big toe is affected most often, accounting for half of cases.[3] Other joints, such as the heels, knees, wrists and fingers, may also be affected.[3] Joint pain usually begins over 2–4 hours and during the night.[3] The reason for onset at night is due to the lower body temperature then.[1] Other symptoms may rarely occur along with the joint pain, including fatigue and a high fever.[1][3]

Long-standing elevated uric acid levels (hyperuricemia) may result in other symptomatology, including hard, painless deposits of uric acid crystals known as tophi. Extensive tophi may lead to chronic arthritis due to bone erosion.[4] Elevated levels of uric acid may also lead to crystals precipitating in the kidneys, resulting in stone formation and subsequent urate nephropathy.[5]

Cause

High levels of uric acid in the blood (hyperuricemia) is the underlying cause of gout. This can occur for a number of reasons, including diet, genetic predisposition, or underexcretion of urate, the salts of uric acid.[2] Renal underexcretion of uric acid is the primary cause of hyperuricemia in about 90% of cases, while overproduction is the cause in less than 10%.[6] About 10% of people with hyperuricemia develop gout at some point in their lifetimes.[7] The risk, however, varies depending on the degree of hyperuricemia. When levels are between 415 and 530 μmol/l (7 and 8.9 mg/dl), the risk is 0.5% per year, while in those with a level greater than 535 μmol/l (9 mg/dL), the risk is 4.5% per year.[1]

Lifestyle

Dietary causes account for about 12% of gout,[2] and include a strong association with the consumption of alcohol, fructose-sweetened drinks, meat, and seafood.[4][8] Other triggers include physical trauma and surgery.[6] Recent studies have found that other dietary factors once believed associated are, in fact, not, including the intake of purine-rich vegetables (e.g., beans, peas, lentils, and spinach) and total protein.[9][10] With respect to risks related to alcohol, beer and spirits appear to have a greater risk than wine.[11]

The consumption of coffee, vitamin C and dairy products, as well as physical fitness, appear to decrease the risk.[12][13][14] This is believed partly due to their effect in reducing insulin resistance.[14]

Genetics

The occurrence of gout is partly genetic, contributing to about 60% of variability in uric acid level.[6] Three genes called SLC2A9, SLC22A12 and ABCG2 have been found commonly to be associated with gout, and variations in them can approximately double the risk.[15][16] Loss of function mutations in SLC2A9 and SLC22A12 cause hereditary hypouricaemia by reducing urate absorption and unopposed urate secretion.[16] A few rare genetic disorders, including familial juvenile hyperuricemic nephropathy, medullary cystic kidney disease, phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase superactivity, and hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase deficiency as seen in Lesch-Nyhan syndrome, are complicated by gout.[6]

Medical conditions

Gout frequently occurs in combination with other medical problems. Metabolic syndrome, a combination of abdominal obesity, hypertension, insulin resistance and abnormal lipid levels, occurs in nearly 75% of cases.[3] Other conditions commonly complicated by gout include: polycythemia,lead poisoning, renal failure, hemolytic anemia, psoriasis, and solid organ transplants.[6][17] A body mass index greater than or equal to 35 increases a male’s risk of gout threefold.[10] Chronic lead exposure and lead-contaminated alcohol are risk factors for gout due to the harmful effect of lead on kidney function.[18] Lesch-Nyhan syndrome is often associated with gouty arthritis.

Medication

Diuretics have been associated with attacks of gout. However, a low dose of hydrochlorothiazide does not seem to increase the risk.[19] Other medicines that increase the risk include niacin and aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid).[4] The immunosuppressive drugs ciclosporin and tacrolimus are also associated with gout,[6] the former more so when used in combination with hydrochlorothiazide.[20]

Pathophysiology

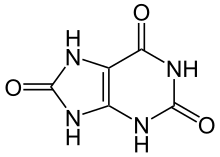

Uric acid

Gout is a disorder of purine metabolism,[6] and occurs when its final metabolite, uric acid, crystallizes in the form of monosodium urate, precipitating in joints, on tendons, and in the surrounding tissues.[4] These crystals then trigger a local immune-mediated inflammatory reaction,[4] with one of the key proteins in the inflammatory cascade being interleukin 1β.[6] An evolutionary loss of uricase, which breaks down uric acid, in humans and higher primates has made this condition common.[6]

Chronic Gout with Gouty Tophi in the soft tissue

Chronic Gout with Gouty Tophi in the soft tissue another angle

The triggers for precipitation of uric acid are not well understood. While it may crystallize at normal levels, it is more likely to do so as levels increase.[4][21] Other factors believed important in triggering an acute episode of arthritis include cool temperatures, rapid changes in uric acid levels, acidosis,[22][23] articular hydration, and extracellular matrix proteins, such as proteoglycans, collagens, and chondroitin sulfate.[6] The increased precipitation at low temperatures partly explains why the joints in the feet are most commonly affected.[2] Rapid changes in uric acid may occur due to a number of factors, including trauma, surgery, chemotherapy, diuretics, and stopping or starting allopurinol.[1] Calcium channel blockers and losartanare associated with a lower risk of gout as compared to other medications for hypertension.[24]

Diagnosis

Gout on X-rays of a left foot. The typical location is the big toe joint. Note also the soft tissue swelling at the lateral border of the foot.

Spiked rods of uric acid crystals from asynovial fluid sample photographed under a microscope with polarized light. Formation of uric acid crystals in the joints is associated with gout.

Gout may be diagnosed and treated without further investigations in someone with hyperuricemia and the classic podagra. Synovial fluid analysis should be done, however, if the diagnosis is in doubt.[1] X-rays, while useful for identifying chronic gout, have little utility in acute attacks.[6]

Synovial fluid

A definitive diagnosis of gout is based upon the identification of monosodium urate crystals in synovial fluid or a tophus.[3] All synovial fluid samples obtained from undiagnosed inflamed joints should be examined for these crystals.[6] Under polarized light microscopy, they have a needle-like morphology and strong negative birefringence. This test is difficult to perform, and often requires a trained observer.[25] The fluid must also be examined relatively quickly after aspiration, as temperature and pH affect their solubility.[6]

Blood tests

Hyperuricemia is a classic feature of gout, but it occurs nearly half of the time without hyperuricemia, and most people with raised uric acid levels never develop gout.[3][26] Thus, the diagnostic utility of measuring uric acid level is limited.[3]Hyperuricemia is defined as a plasma urate level greater than 420 μmol/l (7.0 mg/dl) in males and 360 μmol/l (6.0 mg/dl) in females.[27] Other blood tests commonly performed are white blood cell count, electrolytes, renal function, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). However, both the white blood cells and ESR may be elevated due to gout in the absence of infection.[28][29] A white blood cell count as high as 40.0×109/l (40,000/mm3) has been documented.[1]

Differential diagnosis

The most important differential diagnosis in gout is septic arthritis.[3][6] This should be considered in those with signs of infection or those who do not improve with treatment.[3] To help with diagnosis, a synovial fluid Gram stain and culture may be performed.[3] Other conditions that look similar include pseudogout and rheumatoid arthritis.[3] Gouty tophi, in particular when not located in a joint, can be mistaken for basal cell carcinoma,[30] or other neoplasms.[31]

Prevention

Both lifestyle changes and medications can decrease uric acid levels. Dietary and lifestyle choices that are effective include reducing intake of food such as meat and seafood, consuming adequate vitamin C, limiting alcohol and fructoseconsumption, and avoiding obesity.[2] A low-calorie diet in obese men decreased uric acid levels by 100 µmol/l (1.7 mg/dl).[19] Vitamin C intake of 1,500 mg per day decreases the risk of gout by 45%.[32] Coffee, but not tea, consumption is associated with a lower risk of gout.[33] Gout may be secondary to sleep apnea via the release of purines from oxygen-starved cells. Treatment of apnea can lessen the occurrence of attacks.[34]